Death is an old friend for roguelike enthusiasts. After all, the core gameplay loop is rooted in dying, starting over, and dying better, before eventually securing a hard-won victory to progress further. It’s a battle of attrition that runs on luck and skill, sometimes requiring more of the former than the latter, with randomised encounters and items keeping each playthrough fresh.

In Towa and the Guardians of the Sacred Tree, death isn’t just a guarantee, but woven into the narrative fabric. Much like how indie darling Hades makes it a thematic fit with an underworld setting and nods to the titular Greek god, the roguelite adventure – a sub-genre featuring traditional roguelike elements, hybrid play styles or mechanics, and permanent improvements that offer an advantage in subsequent runs – entrenches its storytelling in time travel, offering a metaphorical means to cheat death in some capacity.

It’s the first sign of bold ambition, as developer Brownies Inc. looks to breathe new life into the well-trodden rinse-and-repeat experience. While it shares commonalities with its roguelite contemporaries, most notably Hades, on the surface, there are moments of ingenuity that point to its promising potential and nudge it toward a unique identity rarely seen in the genre. The inconsistent momentum, however, puts it more as a diamond in the rough than an instant classic, which is a shame.

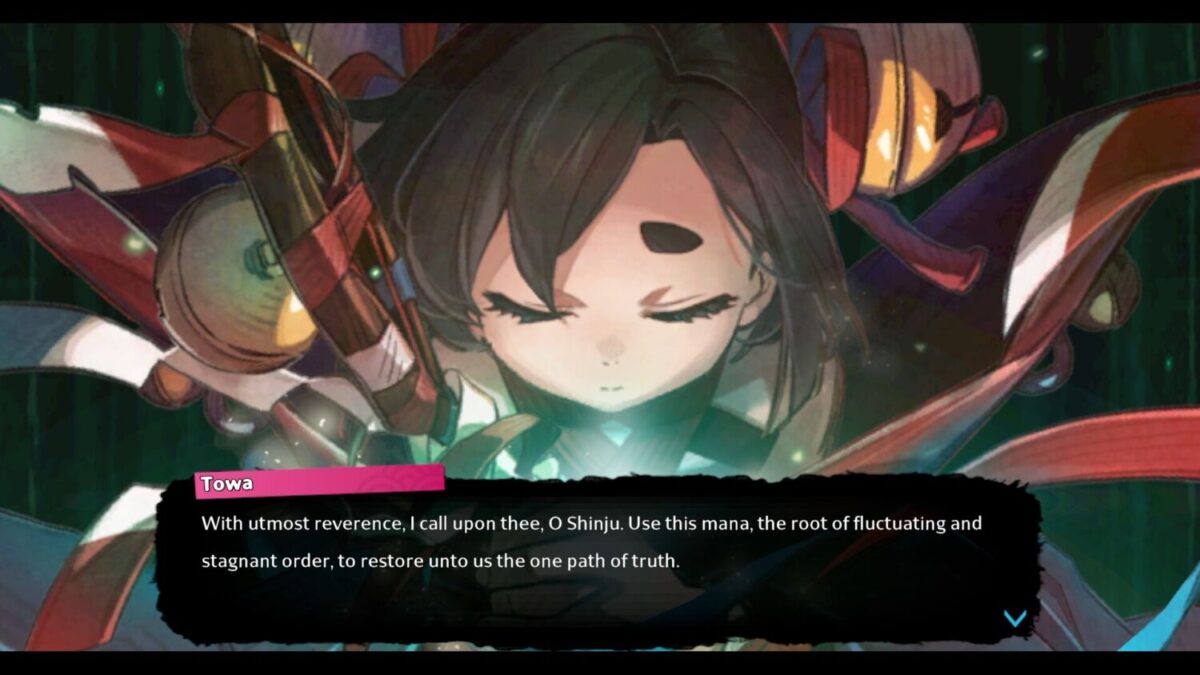

Driving the story is Towa, a scion of a god and guardian of Shinju Village, who sets out to protect the latter against a horde of evil spirits, as a dark god consumes the surrounding land with an evil miasma. Eight villagers, known in-game as the Prayer Children, accompany her on this journey and are later banished to another dimension in an all-out battle, leaving Shinju in a time bubble.

The next time players head out on a Journey (that’s a capital ‘J’), two of them will team up to wreak havoc on enemies. The first takes on the role of the Tsurugi, a frontline warrior assigned to the “sword” moniker, while the other lends assistance as a Kagura, denoted as a magic staff. Here’s the catch – both fighters can be controlled at the same time, bringing Square Enix and Jupiter’s action RPG The World Ends With You to mind, and allowing for the use of twin-stick controls.

No matter the pick, each character comes with a kit tailored to their strengths and weaknesses. The cool-as-cucumber Shigin, for instance, complements passive play styles with long-ranged slicing projectiles as his primary attack, and is more susceptible to damage at close range, while the paper hat-wearing Origami strikes hard at the cost of attacking speed, making her a better fit for solo bosses. In the same vein, the nimble Mutsumi rewards aggression with her flurry of strikes, but it’s easy to be carried away by it, with the spinning attacks of the beefy, bipedal koi Nishiki (yes, you read that right) adding a smooth, flashy touch to combo-chaining, leaving him open to interruption.

Assign them as a Kagura, and it’s a different loadout altogether. Instead of fixing their roles, Towa and the Guardians of the Sacred Tree invites players to switch the companions around and equip them with spells – even if the Kagura abilities are less diverse and offer repeated options (the Tsurugi skillset is unique to the individual, so there won’t be a crossover). After reaching a certain point in the game, Towa will also become playable in the Tokowaka story mode, unlocking access to a nimble-footed experience that prioritises attacking speed over power. The difference between Towa and each of the Prayer Children translates well into combat, both mechanically and feel-wise, such that no two characters can be played entirely in the same way.

The Quick Draw feature completes the equation, forcing players to swap between two swords mid-fight. Here, the Tsurugi wields two blades: the Honzashi and Wakizashi, granting them a secondary moveset. With Shigin and Mutsumi, this means the ability to cast a shockwave or perform a second attack, respectively, in a specified area, on top of their other attack, and only one sword can be equipped at a time. Use it enough times in a row, and the blade will wear down and eventually break, opening up the window for a switcheroo.

Pressing on with a dull sword will reduce damage significantly, but activating Fatal Blow – a special ultimate attack that consumes a mana bar charge, indicated in yellow – restores the weapon durability metre back to full. It’s a neat system that constantly keeps players on their toes, as they balance and navigate between the different battle elements, eliminating the reliance on button-mashing.

The ensemble cast presents some drawbacks, however. Towa and the Guardians of the Sacred Tree inherently suffers from the common issue of power imbalance due to the character’s varying kits, so some of them are more dependent on the sword-swapping mechanics than others. There’s also noticeable input lag at times, which can prove deadly in a fast-paced, reflex-based title like this, especially since foes are free to disrupt attacks here. Synergy is another concern – while the roster gives the impression of flexible team compositions and experimentation, not everyone is always playable as part of the overall story (no spoilers here!), limiting tag-team options and, in turn, affecting efficiency in battles, since certain attacking styles don’t gel well together.

The uneven playing field is partially remedied through a stat levelling system and a smithing mechanic that lets players craft better-quality swords. Taking place over 10 stages, the latter puts them through quick time events (QTEs) for different steps of the process, from fitting the metal parts together (Tsukurikomi) to heating the blade in the forge (Yaki-Ire), complete with intricate customisation that extends to modifying six different parts of the sword, lowering or improving certain stats, and choosing a name and the final finishes for it, which can be equipped across all eight Prayer Children.

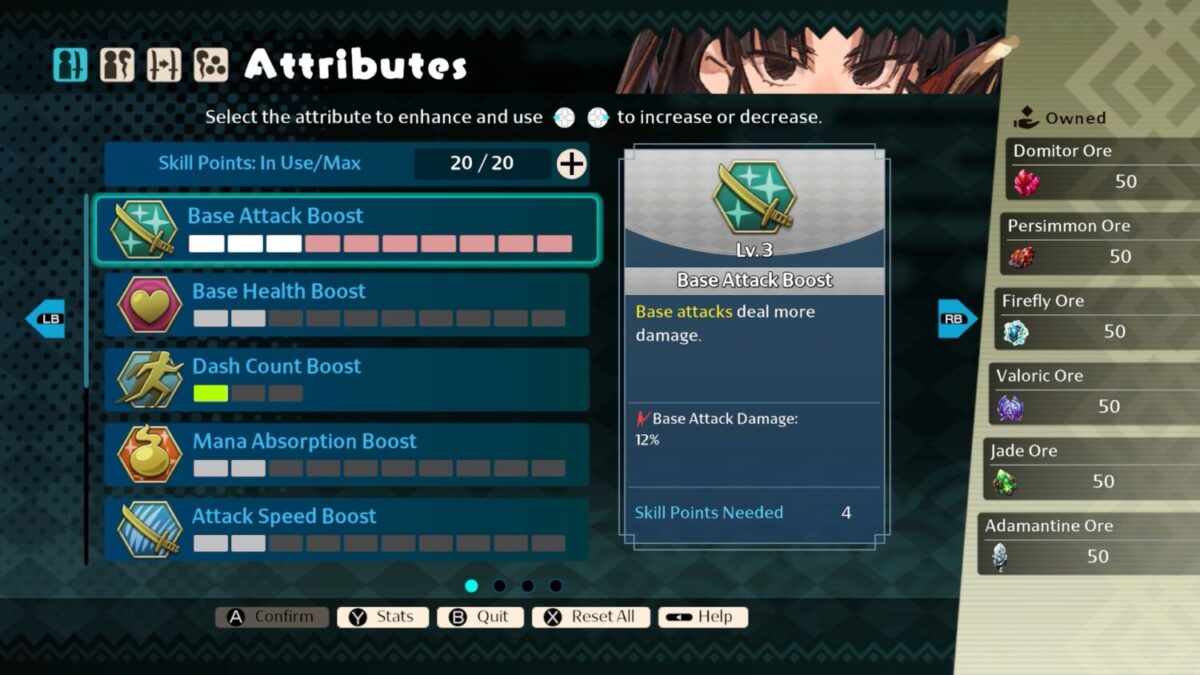

As for character attributes, Towa and the Guardians of the Sacred Tree categorises them into Base Attack, Base Health, Dash Count, Mana Absorption, and Attack Speed, plus an additional Movement Speed in the playable Towa mode. Upgrading them requires Firefly Ores, also used to unlock new Kagura spells, with Kagura staff inscriptions granting boosts to various stats, including Tsurugi or Kagura health, backstab damage, spell cooldown, and more.

Coupled with Shinju’s Virtue – which unlocks and enhances extra perks like revives, reset chances, increased health recovery, and the like – and a favouring system that raises the likelihood of obtaining a specific Grace, power-ups with different rarities that introduce special effects such as life steal, projectile deflection, or the ability to unleash lightning, players can start a new playthrough stronger and better-equipped than before, although luck still factors into victory.

If these elements prove familiar, it’s because the Hades influence permeates strongly here. Towa and the Guardians of the Sacred Tree inherits the fundamentals of a dungeon crawler, where players clear out an enemy-infested room as quickly as they can, pick their preferred Grace (basically the game’s version of a Boon), presented as cards, enter the next domain, and defeat an area boss. Non-combat encounters are scattered throughout, offering a respite from slashing action in the form of bonfires, which include a healing pool and an opportunity for characters to interact, hot springs and food stalls that reward temporary perks, and a store to purchase extra abilities or buffs.

After several stages, a final, more threatening boss stands at the finish line, alongside a number score that appears at the end of every level. Unlike the rank system in, say, the Devil May Cry games, where an ‘SSS’ indicates an exceptional performance, it hardly means anything here – the higher, the better goes without saying, but the determining metric remains unclear. If it’s purely timing, characters with a low damage output are naturally at a disadvantage, prompting players to invest only in attack power, which dilutes the experience of toying with different builds. The number of consecutive combos, or a combination of both, perhaps? Nobody knows. Ultimately, the score is a superfluous addition.

Again, death is all part and parcel of the experience, and the game promises that in spades. Towa and the Guardians of the Sacred Tree doesn’t know the definition of mercy and can be extremely unforgiving at times, aligning with the persistent nature of roguelites, which is only to be expected. What’s not, though, is how it punishes failure brought on by its own design flaws that lie beyond a player’s control, especially in the starting stages. Depending on their luck, a run can last north of 45 minutes, and the reluctance to repeat the long process is exacerbated by one-hit bosses like the Non-Noh, a tight reaction window, and arguably the worst offender, poor contrast of visual elements, where red indicators are placed against a, wait for it, deep red background.

See, part of the genre’s appeal stems from studying an enemy, recognising their attacking patterns, learning when to strike back or play defensively, and eventually, securing a hard-earned victory. The former two factors already make it difficult to enjoy this process, particularly with combo-heavy and fast-moving bosses that are best countered with i-frames, or invincibility frames, turning players invincible for a brief amount of time when certain actions are performed (Fatal Blow, in this context). The lack of visibility proves to be a crutch when keeping track of the hectic on-screen action, too.

There are no accessibility options to change the visual elements, either, and it certainly doesn’t help that story progression is locked behind successful runs – while a lower difficulty level is available, enemies aren’t weakened from the get-go, only with each failed Journey. At best, completing a run sparks relief and quick-fading satisfaction; at worst, it feels like an arduous chore. The co-op experience reveals even more cracks in the gameplay, as it uses the same colour to indicate charge attacks for both the Kagura and Tsurugi, gracing the battlefield with more messy activity. Additionally, the second player will automatically step into the Kagura role, which involves casting two spells and a whole lot of waiting around.

Instead, the charm of Towa and the Guardians of the Sacred Tree is in its characters, and oddly, the domestic moments. Each of the Prayer Children looks distinctive enough to stand on their own, with unique quirks livening up their characterisation. Nishiki and the easygoing shiba inu incarnate Bampuku, for example, represent the fun of breaking the mould, while still honouring the game’s Japanese roots (both the koi and shiba inu hold cultural significance), and it’s always heartening to witness the characters bond over the bonfire in between the combat encounters – be it good-natured ribbing or deeper conversations about life.

Notably, the difference between Bampuku’s Japanese and English voices is jarring, with the former taking on a cute, bubbly tone versus a deeper, more mature one. The passing character lines, which trigger mid-battle or when players enter a new room, could also welcome more variety, as they get repeated fairly often in longer runs, while Rekka’s devoted, overprotective follower archtyping leaves much to be desired.

In Shinju Village, some of the NPC interactions prove equally entertaining, making it easy to crack a smile at the villagers’ antics. At the beginning of the game, access is only granted to the blacksmith, dojo, shrine, and general shop, but as players progress through the story, more features and locations will be available, including the ability to accept requests, construct or upgrade buildings to unlock better, more premium options, eat at a restaurant for temporary stat boosts, and fish, which is as relaxing as it’s productive, collecting Fishing Points that can be exchanged for various items by talking to fishers.

The efforts of Towa and the Guardians of the Sacred Tree to go against the grain deserve credit, with its time travel premise and two-weapon, dual-role mechanics bringing an intriguing spin on traditional gameplay. As a roguelite, however, it loses the edge that endears the genre to many: a sense of satisfaction rather than frustration, the enthralling battle high, the enjoyment in unpredictability and experimentation, and an intuitive system that clicks perfectly in place. An awkward child of innovation and inspiration it may be, but sincerity is never in short supply.

GEEK REVIEW SCORE

Summary

Towa and the Guardians of the Sacred Tree is a bold riff on the roguelite genre that explores some interesting ideas, but falls short of its sleeper-hit potential.

Overall

7.8/10-

Gameplay - 7/10

7/10

-

Story - 7.5/10

7.5/10

-

Presentation - 8.5/10

8.5/10

-

Value - 8.5/10

8.5/10

-

Geek Satisfaction - 7.5/10

7.5/10